In a few short lines, the Federal Reserve has set the stage for a quiet shift in central banking.

For the past thirty years the orthodoxy has been that central banks should focus on controlling inflation, targeting a rate (normally 2%) over a key policy horizon (often 18 months to two years ahead, but sometimes undefined). In his address to the annual Jackson Hole monetary policy symposium, Fed Chair Jerome Powell signalled a break with that orthodoxy by announcing that the Fed would now adopt “a flexible form of average inflation targeting” (our emphasis).

Rather than targeting a 2% inflation rate, the Fed will now “seek to achieve inflation that averages 2% over time”. In other words, it will set policy such that a period in which inflation undershoots its target is followed by one in which it overshoots. A subtle shift, perhaps, but one that reflects a clear break from the past – given a period of below-target inflation over the past few years, it follows that a burst of above-target inflation will not just be tolerated, it will actively be targeted.

You can read more about the Fed’s shift as it relates to the US here. However, it raises two broader questions: will other central banks follow the Fed’s lead, and what are the market implications?

Last year we published a piece arguing that it would be wise for central banks to end their fixation with precise inflation targets. It is worth revisiting in light of the announcement by Jerome Powell. The economic backdrop has, of course, been reshaped by the pandemic but, if anything, that only serves to strengthen the argument we made 12 months ago.

To cut a long story very short, central bank objectives have evolved throughout history, responding to the major challenge of the time – from funding wars to defending exchange rate pegs. In the 1980s, the major challenge was fighting inflation. But that battle has been won and, with deflation now arguably a bigger threat, a regime that is more tolerant of higher inflation makes sense.

Other central banks are likely to follow the Fed’s lead. In fact, the Bank of Japan moved ahead of the Fed; since 2016 it has pledged to continue expanding the monetary base until core CPI inflation exceeds 2% and “stays above that target in a stable manner”. We argued last week that the ECB will probably adopt a similar approach when its monetary policy review concludes next year. And while the Bank of England may be less likely to adopt an average inflation target, at least in the near-future, its mandate arguably already gives it greater scope than the Fed had to tolerate higher inflation.

The market implications will depend in part on how successful central banks are in generating inflation overshoots to compensate for inflation undershoots – or, perhaps more importantly, how successful markets anticipate they will be.

The bond market has so far taken the Fed at face value; inflation expectations have increased and, with nominal US bond yields anchored by ultra-loose monetary policy from the Fed, real yields have fallen. This represents a form of financial repression that is likely to persist as economies work off the additional debt incurred as a result of the pandemic. It is an environment that is likely to be good for the price of risky assets, but terrible for anyone trying to generate investment income.

In practice, boosting inflation to compensate for periods of undershooting is likely to be easier said than done. In the near-term, sizeable output gaps will continue to bear down on inflation in most places. And beyond this, many of the structural forces that have combined to flatten Phillips Curves over the past decade or so are likely to persist into the future. We will have more to say about the medium-term outlook for inflation in a forthcoming Focus (which forms part of a series on “Economies after Covid”).

Without giving too much away, a key conclusion we reach is that some countries face greater medium-term inflation risks than others. It is difficult to envisage a sustained period of significantly higher inflation in the euro-zone and Japan, but the picture is rather different in the US, and perhaps in the UK too. More on that in due course.

In case you missed it:

- Our Chief Markets Economist, John Higgins, puts the recent swings in the dollar in historical context.

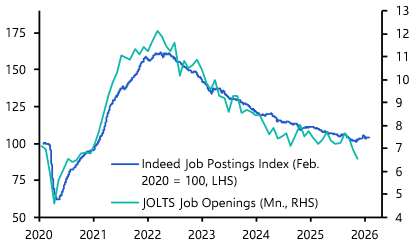

- Our Senior US Economist, Andrew Hunter, takes stock of the recovery in the labour market so far – and explains why service sector weakness will slow progress from here.

- Our Senior EM Economist, Edward Glossop, has published our latest Financial Risks Monitor, which argues that while risks in most countries are low, pockets of vulnerability persist.