There are growing concerns in some corners of the market about the size and scope of government and central bank support packages. Some of these concerns rest on a belief that recessions are necessary to “cleanse” the system of inefficient companies. But this pre-Keynesian approach to economics belies the fact that without huge policy support the scale of the economic downturn – and the associated social and financial costs – would have been even greater than they already are. Faced with the prospect of huge collapse in demand, the response of governments and central banks has been the right one.

At the same time, however, this course of action is not without risks. Two concerns are starting to gain more attention. The first is that a huge injection of policy stimulus will eventually lead to a pick-up in inflation. Concepts like helicopter money and deficit monetisation have entered the mainstream, invoking images of Weimar Germany. The second is that the costs of providing fiscal support will lead to an unsustainable rise in debt. These concerns are inter-related, since one way of eroding debt burdens over time is through higher inflation.

What should we make of all this? If current policies are kept in place then the threat of higher inflation at some point in the future becomes significant, either because aggregate demand rebounds and economies return to full employment, or because inflation expectations rise and we face the spectre of stagflation.

But this point remains a long way off. Japan’s experience shows how difficult it can be to generate inflation in a world of flat Phillips’ Curves and where inflation expectations have become entrenched at low levels.

What’s more, when this point does arrive, the authorities will still have the ability to withdraw support and tighten policy. Central banks can destroy the commercial bank reserves that have been created as part of the latest round of asset purchases (so QE becomes QT), and they can raise interest rates or reserve requirements. Governments can tighten fiscal policy.

Admittedly, we could still end up with higher inflation if governments and central banks actively pursue this as a policy choice, or if they make policy mistakes. Both are possible. Timing the withdrawal of policy stimulus will be difficult; central banks may come under political pressure to maintain support (particularly in a world of higher public debt burdens); and once it becomes acknowledged that the monetisation of debt is acceptable in certain circumstances it may become harder to reverse course.

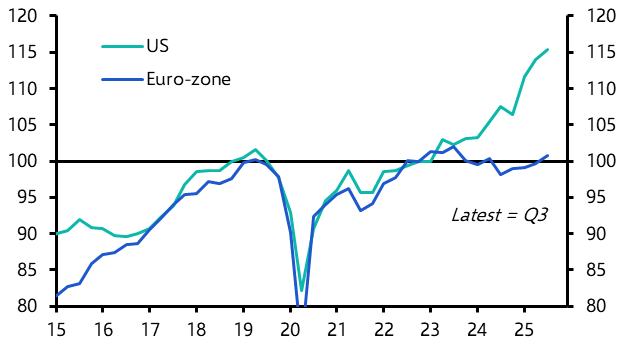

But three points are worth bearing in mind. First, in any of these scenarios the most likely outcome would be a period of moderately higher inflation rather than rampant price increases. The hyper-inflation invoked by images of Weimar Germany tends only to come as the result of political and institutional breakdown. Second, this is not an immediate threat – in most countries the disinflation pressures caused by the current downturn are likely to dominate for several years to come. And third, the risks are spread unevenly across countries. It is easier to envisage a bout of inflation in the US or UK over the next decade or so than it is the euro-zone, where institutional structures and regional imbalances tend to embed disinflation.

What about the risk that support programmes lead to an unsustainable rise in debt burdens? There are two aspects to this. The first is a problem with firms that are not viable having taken on too much debt due to the bail-out measures (e.g. bank loans backed by government guarantees, central bank purchases of corporate bonds and so on). Emergency support has propped up these firms for now, but we could see a painful period of adjustment once it is withdrawn. This does not mean that the policy itself is wrong. For every insolvent firm that is propped up, several viable firms are likely to have been saved. But it does mean that we could see a rise in corporate defaults as support is scaled back.

The second aspect is that the fiscal cost of the various support measures could lead to an unsustainable rise in public debt burdens. We tackled this issue in detail in a piece published last week. A key point is that the past decade shows how, in certain circumstances, governments can sustain relatively large public debt burdens without causing a meltdown in bond markets. This is most likely to be true of countries that issue debt in their own currencies. Fiscal risks are therefore greater in smaller EMs that still rely on dollar funding and euro-zone countries where national central banks can’t stand directly behind sovereign bond markets. But the governments of most countries, including the US, UK, Japan and China, are likely to be able to absorb the fiscal costs of the crisis without triggering a rise in borrowing costs that would cause debt burdens to spiral out of control.

None of this means that the crisis will not incur real costs or require difficult choices to be made in the future. But events will play out in different ways in different countries that don’t fit easily into the one-size-fits-all framework that dominates most commentary. Above all else, the failure to respond to a huge collapse in activity and output with substantial policy loosening would have entailed even bigger economic, social and financial costs today.

In case you missed it:

- Our Chief Europe Economist, Andrew Kenningham, argues that last week’s German Constitutional Court decision highlights future risks to the euro-zone.

- Our Senior US Economist, Andrew Hunter, warns that a state and local government cash crunch could worsen America’s recession.

- And Gabriella Dickens looks at the challenges of measuring inflation during lockdowns.