The sharp fall in oil prices over the past month or so has led to several questions about the implications for the global economy.

We’ve written lots on this subject, including how central banks might respond and why the major oil producers are now better positioned to weather a fall in prices than they were a few years ago. We have also set out how OPEC is likely react and why we expect oil prices to remain under pressure in 2019.

From the perspective of the world economy, the textbooks suggest that a fall in prices should be positive for global growth. This is because it transfers income from oil-producing economies (which have high marginal savings rates) to oil-consuming economies (which have low marginal savings rates). So, on the face of it, the drop in oil over the past few weeks should be a welcome development amid a flurry of otherwise gloomy news. However, the economic theory comes with two important caveats in practice.

The first relates to timing. When oil prices fall, the losses are concentrated in a small number of oil producing economies but the benefits are dispersed over a large number of oil consuming economies. The drag on activity in the former may be felt relatively quickly, as energy firms mothball investment projects and governments and consumers are forced to tighten their belts. In contrast, the boost to activity in the latter can take longer to materialise since consumers may need to be persuaded that lower prices aren’t a flash in the pan before adjusting their behaviour.

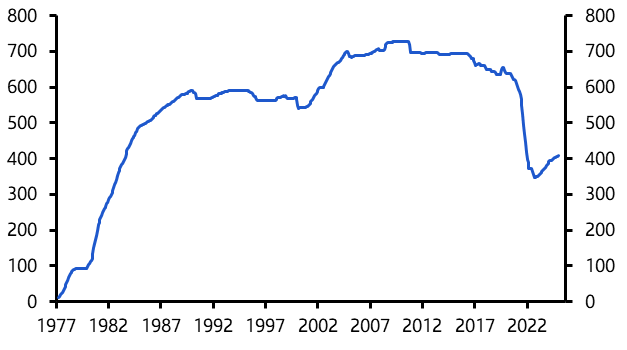

The second caveat is that, while lower oil prices should ultimately be beneficial for world growth, this is typically swamped by other things. In particular, a drop in oil prices is often driven by more fundamental concerns about the health of the global economy. By shifting income from savers to spenders, the fall in prices acts as a form of automatic stabiliser that helps to cushion any slowdown in world growth. But past form suggests that this doesn’t tend to prevent it from weakening altogether in the short-term. Indeed, as Chart 1 shows, drops in oil prices typically coincide with slowdowns in the global economy.

Chart 1: World GDP Growth & Change in Brent Oil Price (% y/y)

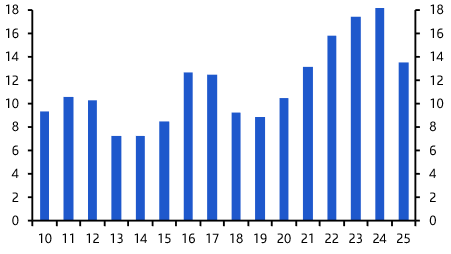

It’s worth noting that the recent drop in prices is relatively small compared to past falls. (See Chart 2.) It’s also the case that the oil markets can be fickle – as recently as three months ago the debate was all about whether a combination of a strong US economy and sanctions on Iran would push prices back above $100 (to the credit of our Commodities team, we argued that oil would instead fall – as it has since done). Even so, it is still the case that the drop in oil prices adds to a growing list of indicators that point to a slowdown in the global economy over the next six to twelve months.

Chart 2: Change in Brent Oil in Previous Price Slumps (%-pts)

In case you’ve missed it:

(Requires login)

- Our Senior Economic Adviser, Vicky Redwood, takes a deeper look at Japan’s debt dynamics and examines the lessons for other countries.

- Our Latin America Economist, Edward Glossop, outlines five things investors should watch for as Mexico’s new president takes office.

- Our markets team take assess the causes and consequences of the rising corporate credit spreads.

Number of the Week

-98%

The drop in US exports of soy beans to China over the past year. Read our detailed assessment of the effect of increased tariffs on US-China trade here.