The climate summit hosted by President Biden last month produced a series of ambitious targets for cutting carbon emissions by major economies. This included the US itself, which pledged to halve emissions by 2030 relative to 2005 levels and achieve net zero emissions by 2050. What effect will all of this have on economic growth?

Targets are a useful and necessary political tool, but what really matters is the extent to which policies shift to meet them. The usual pushback is that the necessary measures will require governments and electorates to accept weaker rates of economic growth. This may be a common view, but it doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny.

When thinking about the economic consequences of “greening”, it’s helpful to separate out the effects on demand and supply.

A major challenge facing policymakers prior to the pandemic was sustaining sufficient levels of aggregate demand to keep economies at full employment. In these circumstances, any green spending by either the public or private sector should provide a short-term boost to economic growth. Accordingly, from a demand perspective, efforts to “green” economies should be viewed as part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

There is greater contention around the effects on the supply-side of economies. Some argue that any attempt to “green” the behaviour of consumers or firms through taxes or legislation will lead to a misallocation of resources and result in lower levels of GDP than would otherwise be the case.

Yet it’s important to bear in mind that in economics the costs and benefits of policies are not always fully captured in measures such as GDP. This is particularly true in areas like the environment, where large externalities in the form of pollution diminish overall welfare but are not necessarily reflected in lower levels of output. Conversely, measures such as the introduction of carbon taxes should lead to a better allocation of resources from the perspective of social welfare, although this may not be reflected in measured GDP.

What’s more, to the extent that measures to reduce carbon emissions are reflected in GDP, the effect may not necessarily be negative. There are two ways in which policies to tackle climate change could set economies on a lower path of output. The first is if they divert firms from using cheaper inputs to more expensive ones, thus denting company profits and weighing on investment and productivity. The second is if they render large amounts of the existing capital stock obsolete.

But technological advances mean that the costs of renewable energy have fallen a long way in recent years, therefore reducing the risk of a productivity-sapping rise in input prices. (See Chart 1.)

Chart 1: Cost of Different Types of Energy* ($/MWh)

Source: Capital Economics. *The net present value of the unit-cost of electrical energy over the lifetime of a generating asset.

At the same time, while reducing emissions will require upgrading equipment and building new infrastructure, this can be phased in over time without making large amounts of the existing capital stock redundant. What’s more, this transition can (and should) be supported by governments, who can currently issue long-term debt at negative real yields. This should limit any economic damage. In fact, it’s possible that investment in low carbon technologies spurs innovations that produce positive spillovers to other sectors and therefore lead to a broader rise in productivity growth. Research by academics at the LSE has found a widespread application of low-carbon innovations in other sectors.

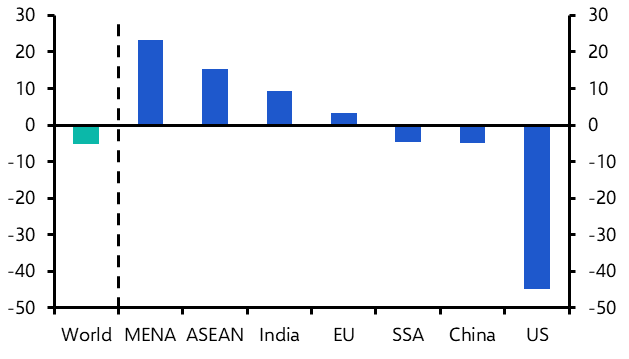

Stepping back, one point that often gets missed in the debate around climate change is that the link between carbon emissions and global GDP growth has already weakened. (See Chart 2.) This may in part reflect a slowdown in emissions growth in China from previously very high rates. But even so, the point remains that the link between emissions and GDP growth is neither absolute nor constant.

Chart 2: World GDP & Carbon Emissions (% y/y)

Sources: Our World in Data, Refinitiv, Global Carbon Project

Ambitious climate targets will require substantial changes to the current structure of economies, and there will be winners and losers at country and sector levels (we’ll have more to say on this in future research).

But the economic challenge posed by climate change isn’t a zero-sum game – the view may be commonly held, but cutting global emissions doesn’t mean automatically accepting a lower path of global GDP.

In case you missed it:

- Later this week we will be hosting a webinar on how to track the evolution of inflation pressures as lockdowns are lifted. All are welcome – register here.

- Our China team has published in latest outlook in which they argue that the economic rebound will soon start to level off.

- Our Senior Global Economist, Simon MacAdam, looks at the inflation lessons from the 1970s and asks whether history is about to repeat itself.