Neil Shearing

Group Chief Economist

The acute phase of last month’s banking crisis — which some, channelling the US College Basketball tournament, have dubbed “March Madness” — has passed. The sense of panic has abated and markets have calmed. Measures of financial stress have fallen and, while there have been big movements in different sectors of the equity market (bank stocks are still down by more than 10%), the S&P 500 is now higher than it was on 8th March, when problems at SVB first emerged.

The most pressing question now is the extent to which banks respond by further tightening lending conditions for households and businesses. The best indication of this will come from the senior loan officer surveys that are conducted by the world’s major central banks. But these aren’t particularly timely and the effects of last month’s crisis will only start to show in the Q2 surveys, which won’t be published until July.

In the meantime, we will have to decode signals from the monthly data on monetary aggregates and watch the business surveys for evidence that firms are finding it harder to access credit. Given that credit is a coincident (rather than a leading) indicator, tighter lending conditions will show up first in the usual activity data too.

It may take years before the full account of the crisis is written but even now, key takeaways have emerged from the events of recent weeks. Three stand out.

The first is that while it’s tempting to label the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and Credit Suisse as “idiosyncratic” events, all three have a common thread in management failures that were exposed by the end of the era of cheap money. This is a risk that we flagged more than six months ago. Models and practices in financial institutions were premised on the belief that the period of ultra-low interest rates would continue. This resulted in SVB failing to adequately hedge interest rate risk, and some (though, in the case of Europe, not all) central banks failing to sufficiently test banking sector vulnerabilities to higher rates.

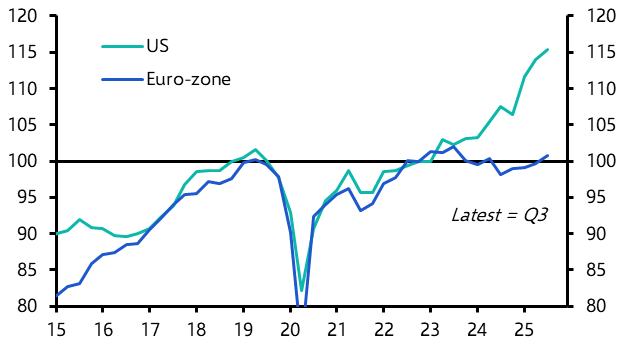

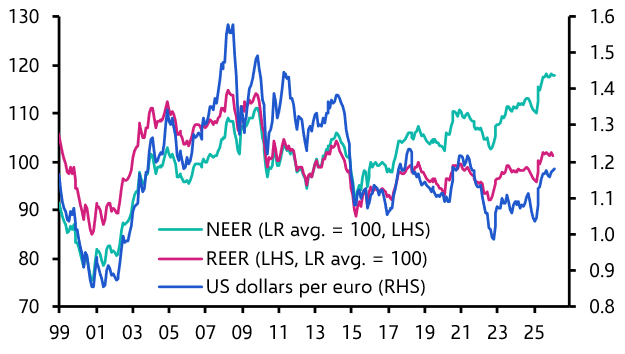

While the immediate fallout from SVB has abated, the full effects of the aggressive tightening in monetary policy over the past year have yet to be felt. Fears of a repeat of the financial crisis of 2007-08 were always overdone, but further financial sector casualties are nonetheless likely over the coming months and quarters. Key areas to watch include commercial real estate and the shadow banking sector. Meanwhile, we estimate that more than half of the effect of monetary tightening by central banks in this cycle has yet to be felt in the real economy. All of this points to a rocky remainder of this year.

The second lesson from the past month is that when problems in the financial system do emerge, they spread much more rapidly in a digital world. Bank runs no longer involve long lines outside troubled lenders — they happen in a matter of hours and take place online. The collapse of SVB, which was the second largest bank failure in US history, took place in just 36 hours. Information and speculation — and therefore panic and fear — spread much more quickly in a digital world. Given this, regulators and policymakers have some catching up to do. In particular, given the speed at which events now move, it is remarkable that central bank lending facilities aren’t accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Finally, recent events have served as a reminder that the financial system is inherently fragile. This is nothing new — indeed, an element of fragility is baked into the whole, centuries-old model of fractional reserve banking. But each crisis brings a new twist, and a recent theme has been fragility exacerbated in part by the fact that regulators have been trapped fighting the last battle.

In the early 2000s, the fallout from the tech bubble and various accounting scandals focussed attention on risks from the corporate sector, with the result that vulnerabilities in housing and mortgage markets were missed. Then, as the subsequent housing crisis led to widespread defaults, attention shifted to mitigating credit risks, with the result that interest rate risks were overlooked. It’s a good bet that whatever the cause of the next crisis, it won’t stem from problems managing interest rate risk.

The growing financialisation of economies — combined with the risks inherent in fractional reserve banking — means that banks have become private institutions with the implicit backing of the state. The political and economic consequences of wiping out depositors means that, in democracies, limits on deposit insurance go out of the window when a bank runs into trouble.

One implication is that, to all intents and purposes, we should ignore such limits — in effect, the state has become a guarantor of all consumer deposits. Another implication is that because of the inherent fragility of the system — and the fact that regulators are usually at least two steps behind the curve — banks need to be made safer. The bulwark against crises is to hold more capital — indeed, this is a key reason why we are not facing another ‘Lehman moment’ today. As the memory of the latest crisis fades, calls to loosen capital requirements will inevitably come. They must be resisted.

A final implication, which is closer to home, is that economists must find a way of capturing financial vulnerabilities in their forecasts. This is extremely difficult but it starts with accepting that “black box” models do not adequately capture the complexities of modern economies — what’s required is analysis, judgement, humility and a good knowledge of economic history.

In case you missed it:

- The IMF’s focus on risks around ‘geoeconomic fragmentation’ in its latest WEO underlines how this important issue is further entering mainstream discourse. This dedicated page houses all of our key analysis on fracturing since we began work on it a year ago.

- Following the March CPI report, Deputy Chief US Economist Andrew Hunter explained why the Fed could deliver a final 25bps hike in May.

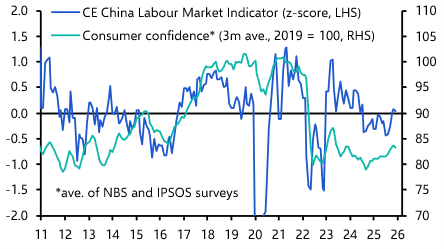

- Our China team will be briefing on the Q1 “data dump” on Tuesday, 18th March to assess the strength of the post-lockdown recovery. You can register here for that session.