This is a time for looking ahead and, in that spirit, you can find all our big calls for this year on the “Key Themes” section of our website. However, it’s also worth pausing to reflect on the state of the global economy as we leave one decade and enter a new one. At first sight, there appear to be several contradictions.

On the one hand, the economic recovery in advanced economies over the past decade, following the 2008 global financial crisis, has been painfully slow. Real GDP in the G7 is now 13% below its pre-crisis trend. What’s more, this has only been achieved with the help of super-loose monetary policy. One consequence of this is that the 2010s ended with a quarter of the world’s sovereign debt trading at negative yields.

On the other hand, labour markets are in good shape, with unemployment at multi-decade lows in many parts of the developed world. And stock markets in several countries – notably the US – are at record highs.

How can we square all of this? A large part of the answer lies in the weakness of productivity growth.

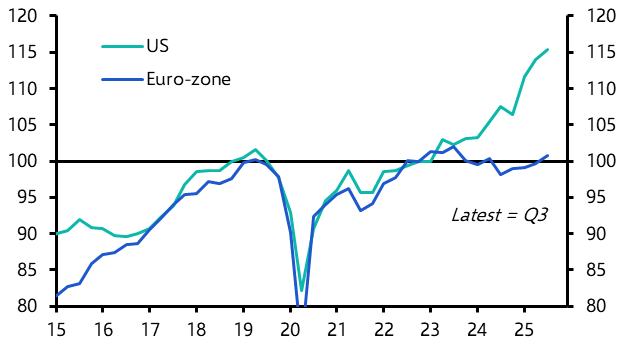

Productivity growth in the G7 has been in structural decline for several years. (See Chart 1.) The weakness of productivity growth has been particularly marked in the UK – output per worker increased by an average of just 0.6% a year in the 2010s, compared to 1.1% a year in the 2000s and 2.1% in the 1990s. But weak productivity growth is not just a UK phenomenon. The past decade has also been one of extremely weak productivity growth in the euro-zone, Japan and (to a lesser extent) the US.

Chart 1: G7 Labour Productivity Growth (10yr rolling average, % y/y)

This helps to explain many of the apparent contradictions at the heart of the global economy. For a start, the weakness of productivity growth has been fundamental to the weakness of overall GDP growth over the past decade. But it also helps to explain the strength of employment growth – since low rates of productivity growth have required firms to hire additional workers in order to raise output.

Low productivity growth also helps to explain moves in asset prices. One consequence of slower productivity growth is that equilibrium real interest rates (or R* in the jargon) have fallen. Lower equilibrium interest rates in turn justify higher asset prices. Viewed this way, asset prices start to look much less overvalued and talk of a bubble in equities begins to sound like a lot of hot air.

The past few weeks have seen lots of crystal-ball-gazing as to what the new decade has in store. One point that tends to be missed is that the state of the global economy at the end of the 2020s will depend to a large extent on whether productivity growth in developed markets starts to recover. This will have an important bearing on the outlook for growth, wages, inflation, interest rates and asset prices. In fact, it’s difficult to think of a single important macro or financial variable that will not be influenced by what happens to productivity.

Economists tend to fall into one of two camps when it comes to productivity. The first contains the techno-pessimists, who argue that the latest wave of technological development, which has been focussed on digital, is fundamentally different from previous waves of technological development and will fail to deliver a meaningful improvement in productivity. The second contains techno-optimists, who argue that it takes time for infrastructure and processes to adapt to new technologies but, once they do, productivity growth will accelerate. In their view, from a productivity perspective, there is no difference between the latest wave of technological development or those in the past. It is simply a matter of time before the full effects show up in the productivity figures.

We’ll have more to say about this over the coming months but, if pushed, we’d side with the techno-optimists. That should mean that trend GDP growth in developed markets accelerates over the course of this decade. However, this outbreak of new year optimism comes with the important qualification that there’s not much evidence that a productivity renaissance is imminent. By the end of this decade the productivity landscape should look a bit better. But for the next couple of years at least, we’re likely to be stuck in a world of low productivity, GDP growth, low inflation and low interest rates.

In case you missed it:

- We’ve published our latest Long-term Global Economic Outlook, which contains forecasts for major economies out to 2050 and incorporates our recent research on globalisation, climate change and technological change. Read it here.

- Our Senior US Economist, Andrew Hunter, argues that President Trump’s deregulatory agenda has so far done little to boost trend economic growth.

- Our Emerging Market Economist, Edward Glossop, takes a closer look at the drivers of the recent spike in EM inflation.