Markets invariably quieten as the year turns, even as important developments continue to shape the macreconomic landscape. Below are three key issues that we’ve been focusing on during the relative quiet:

The first relates to China’s reopening. Julian Evans-Pritchard provides a useful summary here, but the short version is that the rapid dismantling of COVID restrictions has led to a surge in infections that is producing large negative shocks to both supply and demand. The hit to output in the coming months will be substantial but, as Julian argues, fears that reopening will push up inflation in China and the rest of the world may prove misplaced.

The second significant development over the holiday break has been the collapse in the price of European natural gas. The decline has been remarkable both because of its size but also because – unlike events in China – it has received relatively little attention. Prices have fallen from €150 p/mwh in mid-December (and a peak of well over €300 p/mwh in the summer) to just under €70 p/mwh at the time of writing. They now sit below the level when Russia invaded Ukraine.

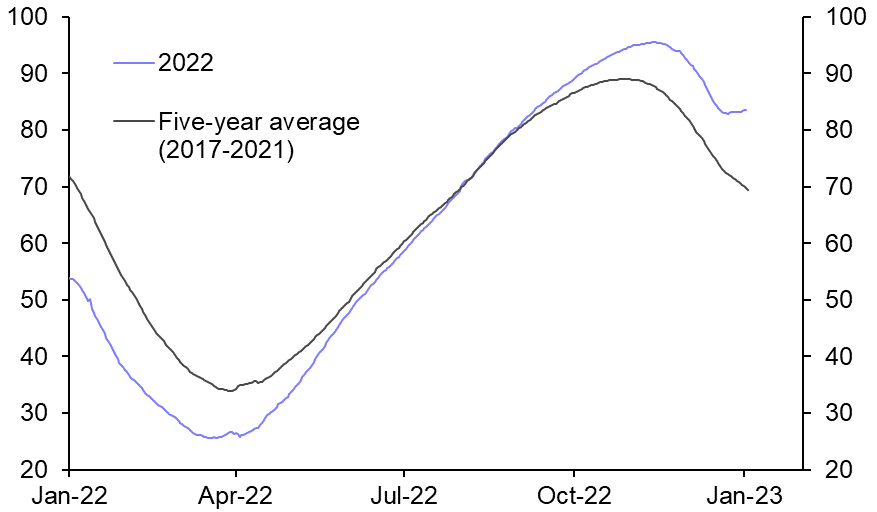

The drop in prices has been caused by an extremely mild winter in Europe. Gas in storage normally falls over the winter months but this year it has actually risen. (See Chart 1.) What happens next will depend to a large degree on the weather in Europe over the rest of this winter (although perhaps we can take comfort from the fact that weather forecasters have a better track record than economic forecasters). Either way we’re one cold snap away from European natural gas prices rebounding.

|

Chart 1: EU Gas in Storage (% Full) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv |

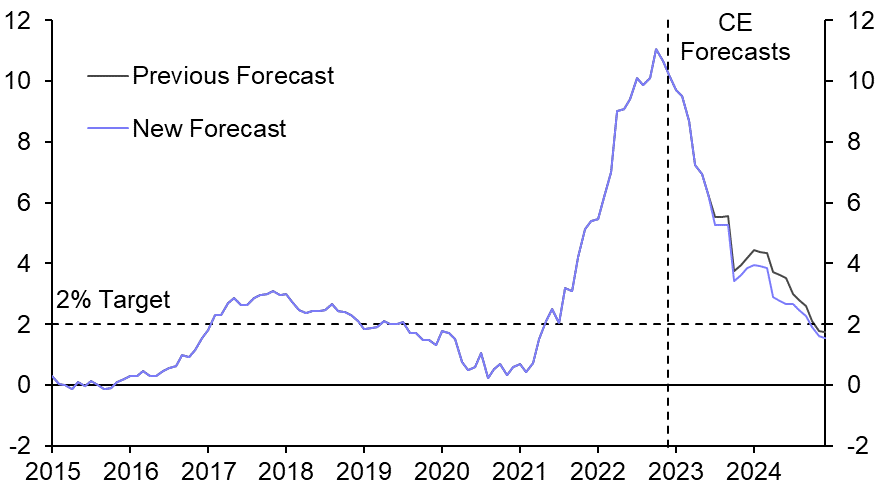

We had expected gas prices to fall back this year, but the scale and speed of the move has been far greater than we had envisaged. Lower natural gas prices will help the fight against inflation in Europe, but the impact on CPI might be smaller than one might have expected given the drop in wholesale prices. We’ve pulled down our forecast for European gas prices to reflect recent moves, but in the case of the UK that means inflation over the second half of this year will be only 0.3%-pts lower than we had anticipated, while inflation in 2024 will be about 0.5%-pts lower. That’s helpful, but looks small when set against current double-digit rates of inflation and the fact that base effects were always likely to pull down headline CPI this year. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: UK CPI Inflation (%) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv |

One reason for this is that government energy support packages prevented the previous surge in wholesale gas prices from being fully reflected in consumer price inflation. Accordingly, if sustained, the recent drop in wholesale prices will remove a difficult choice for governments about how and when to scale back support that was otherwise looming large. The plunge in natural gas prices is unlikely to prevent Europe from sliding into recession. But if it persists, the recession will be milder and the recovery swifter than would otherwise have been the case – and life for the region’s politicians will become a little easier.

We’ve also been watching issues related to potential future developments, rather than anything happening now. Another debate over the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency broke out online before spreading to the mainstream financial press. (This gives you an insight into how economists spend their holidays.) The argument in a nutshell is that, with trade in oil increasingly dominated by China, Russia and Saudi Arabia, this will in time lead to the “de-dollarisation” of global energy trade. This idea was given impetus by a meeting between Xi Jinping, Mohammed bin Salman and the leaders of the GCC in mid-December, at which Xi heralded a “new paradigm of all-dimensional energy cooperation”. Part of this new paradigm, it seems, will be the growing use of the renminbi to settle energy trade between China and the Middle East. This in turn has led to speculation about the rise of the “petroyuan” and the subsequent demise of the US dollar.

This is another example of how global fracturing, which we explored in detail in our Spotlight project last year, has the potential to reshape the economic and market landscape. In the case of the dollar, however, we think the consequences will be less dramatic than many seem to believe.

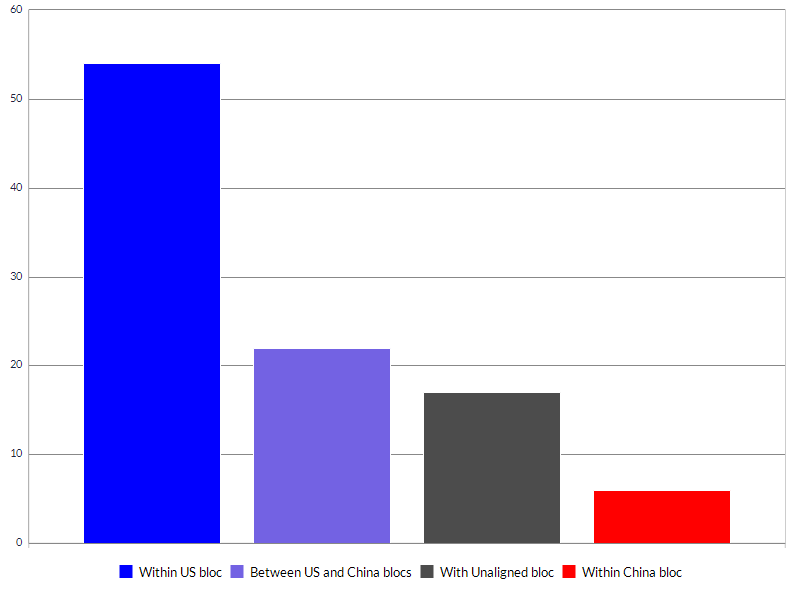

First, while trade between China, Russia and the Middle East is growing, it still accounts for only 2% of global trade. Most trade still happens between US-aligned countries, and will continue to be denominated in US dollars. (See Chart 3 – the data for all our Spotlight work can be downloaded here.) Second, China, Russia and the Gulf countries all run large current account surpluses, which will tend to work against them becoming a serious rival to the dollar as a reserve currency (since demand for reserve assets is high, the country with the dominant reserve currencies tends to run current account deficits).

|

Chart 3: Share of Global Goods & Services Trade (%) |

|

|

| Sources: IMF, WTO, Capital Economics |

Finally, as we argue in the Spotlight section on financial flows, the dollar has several things working in its favour. For a currency to be widely used as an international medium of exchange, it must be readily and cheaply available around the world. In turn, that depends on foreigners being willing to hold it in large volumes: in other words, it must function as a store of value.

The dollar is not the only currency that could perform this role. But any alternative would need to share similar attributes: it would be backed by strong and stable institutions, and issued by a central bank that operated an open capital account. What’s more, any currency with these characteristics would have to overcome the strong network effects that underpin the dollar’s global dominance. All of this is likely to work against the emergence of a “petroyuan” on a scale that threatens the dollar’s position.

Fracturing is real, but the forecasts of the dollar’s global demise are premature.

In case you missed it:

- The World in 2023 sets out what we think will be the key economic and market themes this year. We’re holding Drop-Ins this week to answer your questions and highlight the key takeaways from our reports in this series. Sign up here for sessions on developed and emerging economies on Tuesday and/or Wednesday’s briefings on the financial and commodity markets outlook.