And breathe. After a week that brought us a flurry of global data on inflation, GDP and the labour market – as well as the first major central bank meetings of the year – you can be forgiven for struggling to see the wood for the trees.

At first glance, there’s been a stark improvement in the outlook in only a few short months: China’s back, euro-zone data have been looking much better, the US jobs market remains robust even as inflationary pressures retreat, the global policy tightening cycle is slowing and markets have been cheering.

But some perspective is necessary, and last week’s action-packed week drove home a number of crucial points about the state of the global economy and markets.

Economies aren’t out of the woods

If nothing else, the world’s major advanced economies are continuing to struggle, despite what some of the headline data are saying. The euro-zone outlook has undoubtedly improved compared to a couple of months ago, helped in large part by a collapse in natural gas prices – but it’s still in trouble.

We learnt last week that the euro-zone economy grew by a paltry 0.1% q/q in Q4. What’s more, the fact that the euro-zone registered any growth at all was due to another large increase in Irish GDP, a reflection of the tax arrangements of multinational companies rather than genuine economic activity. Without the boost from Ireland, euro-zone GDP would have flat-lined. To make matters worse, the breakdown of GDP, showed domestic demand contracting across the continent as real incomes are squeezed: consumer spending and business investment fell in quarter-on-quarter terms in both France and Spain in Q4. And separate data released last week showed a large fall in German retail sales in December. Headline GDP may be stagnating, but households in Europe are most definitely feeling the pain.

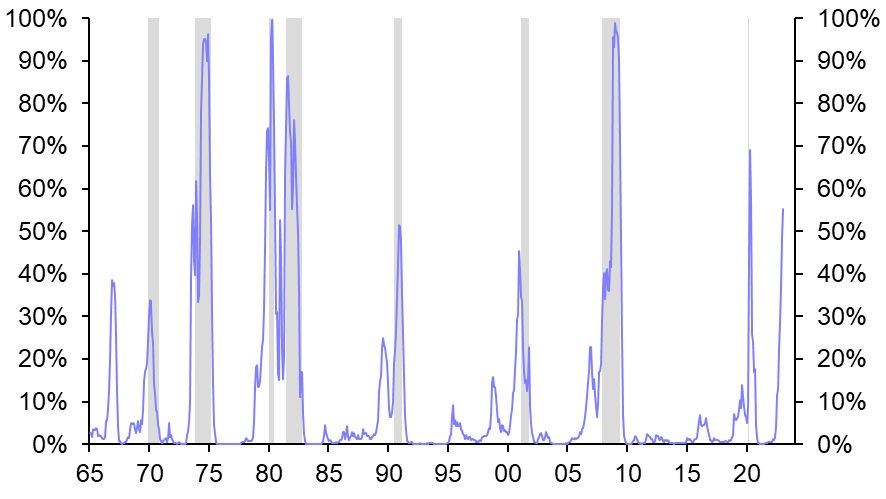

The recent activity data from the US have also been muted. Admittedly, Q4 GDP expanded by a solid 2.9% q/q annualised. But activity weakened steadily through the quarter, and some of the early data from the start of this year have since dropped to recessionary levels. In particular, the new orders component of the ISM manufacturing index fell in January to a level at which a US recession has always followed. Set against that, there are some early signs that activity in the US housing market is starting to bottom out and the ISM non-manufacturing survey was better than its manufacturing cousin. But even so our tracking models suggest that the economy will more likely than not be in recession in three months’ time. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Comp. Model Recession Probability (3m Ahead) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics US Recession Trackers |

Labour markets are holding up – with caveats

The second point that stands out from the recent data dump is the contrast between the broad weakness of activity and the continued strength of labour markets. The most obvious example of this was the monster 517,000 gain in US payrolls in January, which pushed the unemployment rate down to a 53-year low of 3.4%. Admittedly, the sheer size of the gain in payrolls looks suspicious and it’s possible that distortions caused by seasonal factors may have inflated the number. What’s more, not all US labour data have been unambiguously strong: the quits rate has fallen, the Challenger series of layoffs has risen and, most importantly, wage growth is showing clear signs of moderating. Even so, the broad message from the latest data is that labour markets in the US and Europe have so far remained resilient in the face of weakening activity.

The Fed is far ahead of the ECB in the cycle

The final take-away from the past week is that we still think the Fed will be in position to cut rates before year-end. The ECB not so much.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell struck a relatively hawkish tone in the post-FOMC press conference, which stands in contrast to a bond market that continues to rally and, indeed, rallied further following the FOMC meeting. This unwound a little after the payrolls data on Friday, but Fed Funds futures are still pricing in one more 25bps increase in rates to 4.75-5.00% followed by a cut to 4.50-4.75% by the end of this year. When asked how this might resolve itself Powell answered “we’ll just have to see”.

It’s important to remember that no self-respecting central banker would ever indicate that they might countenance rate cuts while still in the middle of a tightening cycle (Powell also let slip that he thought “a couple more” rate hikes might be appropriate). Doing so would risk a self-defeating easing in financial conditions – at a time when they are still attempting to engineer tighter policy.

January’s employment report has muddied the waters and has fuelled concerns that labour market tightness will prevent US inflation from falling on a sustained basis. Our view remains that inflation will fall this year irrespective of what happens to the labour market, and that in any case, labour market conditions will start to soften as the real economy continues to weaken. Accordingly, we continue to think the Fed will move towards the market rather than the market towards the Fed. We’re sticking by our view that US rates will be cut towards the end of this year.

What about the ECB? For all Powell’s hawkishness, the Fed did slow the pace of tightening to 25bps increments. And while the Bank of England raised interest rates by another 50bps last week, changes to the accompanying statement suggested that rates may either have peaked or (more likely in our view) that the future pace of tightening will drop to 25bps. In contrast, the ECB hiked interest rates by 50bps and explicitly signalled one more hike of a similar magnitude next month. This would take euro-zone interest rates to 3%.

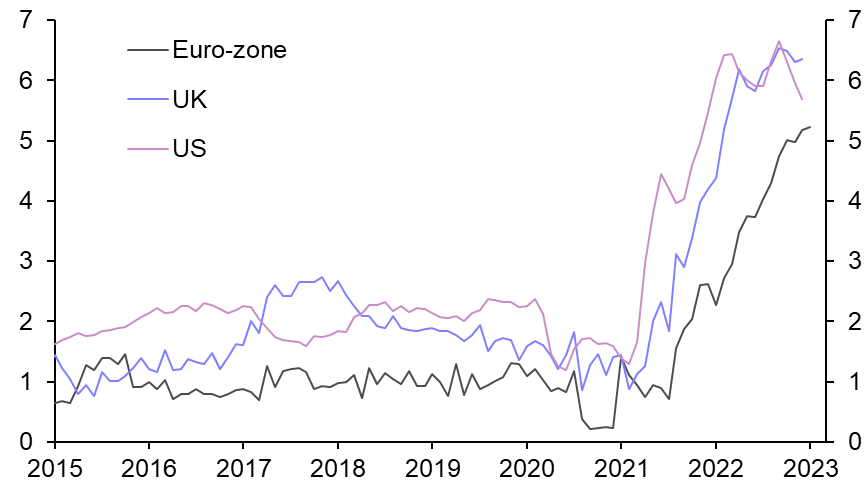

|

Chart 2: Core Inflation (%y/y) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Euro-zone bond markets have been on a similar rollercoaster to those in the US this past week: rallying in the immediate aftermath of the ECB meeting before giving back some of those gains following the US payrolls data. But the key point is that the ECB still has more work to do than other major central banks. This partly reflects the fact that it was later to start tightening than the Fed or the Bank of England. But it’s also because, unlike in the US, core inflation in the euro-zone has continued to accelerate. (See Chart 2.) What’s more, the flip side of lower European natural gas prices is stronger domestic demand. We think that euro-zone rates will peak at 3.5% in this cycle – and whereas the market is now pricing in cuts by December, we don’t expect policy to be loosened until later in 2024.

PS: Thanks for all of your feedback on our new podcast. Please keep it coming. If you’ve not already subscribed you can do so in all the usual places or on our website. New episodes are released every Sunday evening, providing you with everything macro and markets that you need to chart the week ahead.

What you may have missed:

- Deputy Chief UK Economist Ruth Gregory discussed the trend towards fixed-rate mortgages and how it could make life harder for the Bank of England;

- Tom Mathews, a Senior Economist on our Markets team, explained why the reopening rally for Chinese equities may have further to go;

- Ahead of Nigeria’s crunch election at the end of this month, Virág Fórizs from our EM team outlined the country’s near-term economic challenges.