Goods and labour shortages are now the biggest challenge facing the global economy – and central bankers and economic policymakers by extension.

Yet much of the thinking around shortages is confused. In particular, there is a tendency to bracket together all shortages under a common banner, when in practice they are very different in nature.

In a piece published last week, we identified four types of shortages:

- Shortages caused by a scarcity of labour.

- Shortages caused by a pandemic-related increase in demand.

- Shortages caused by pandemic-related bottlenecks in supply.

- Shortages caused by unusual weather patterns.

These are likely to play out in different ways. In most countries, labour shortages continue to reflect frictions around reopening from lockdowns, and difficulties in matching workers that were furloughed or laid off during the pandemic to available jobs. These frictions should ease over time, but there is a risk they are longer lasting in the US, where the nature of labour market support during the pandemic was different to Europe and there is now evidence that some older workers have dropped out of the labour force altogether. In the UK, a tougher post-Brexit approach to immigration could cause labour shortages to persist for longer than in Continental Europe and weigh on potential GDP growth.

The strains in goods markets due to either a pandemic-related surge in demand or bottlenecks in supply look set to intensify over the coming months, although they should also eventually ease as consumption habits normalise. What happens to weather-related shortages is more uncertain although, as our Commodities team has noted, an unusually cold winter in the Northern Hemisphere would keep gas and energy prices elevated.

Crucially, mapping all of this together reveals how shortages caused by these different factors are now feeding off and exacerbating one another. For example, a shortage of transportation workers (labour) is exacerbating bottlenecks at ports and intensifying shortages of everything from furniture to food (goods).

These interdependencies – and the fact that inventory is now extremely low across global supply chains – have created a world trading system that is fragile and vulnerable to shocks that will create shortages in new and different areas. This means that even if strains in goods markets are likely to ease over time as relative prices adjust and demand and supply come back into balance, shortages are likely to both persist and emerge in new areas over the next 6-12 months. This is not an issue that will fade quickly.

All of this begs two questions: how will the economic effects of shortages manifest themselves and how should policymakers respond?

The textbooks say that if demand exceeds supply, then prices will increase to restore market equilibrium. But in practice the actual outcome will depend on the nature of the shortage and the structure of the market in question. If the shortage relates to labour, then the ability of workers to demand higher wages will depend on their bargaining power. If the shortage relates to goods, then the ability of firms to raise prices will depend on their pricing power. In many cases firms “price to market” rather than setting prices at a level that would maximise profits.

For now, while prices of certain goods have surged, the shortages have so far caused only a moderate rise in average core inflation in advanced economies. They are partially manifesting themselves in limits on output instead.

What about the policy response? In most cases the role of governments should be limited to allowing markets to work and relative prices to adjust. In some instances, there is a case for mitigating the distributional costs of this adjustment, for example by easing the burden of higher energy costs on poorer households.

The consequences for financial markets will depend to a greater extent on the monetary policy response. The crucial point here is that central banks should not respond to specific shortages and should only tighten policy if aggregate demand exceeds aggregate supply on a sustained basis.

We expect most major central banks to begin withdrawing policy support over the next year or so, but the pace is likely to be gradual. As things stand, we doubt that an aggressive monetary policy response will be warranted – central banks in advanced economies seem more likely to focus on depressed employment and/or weak core inflation. The key risk here is that shortages persist for longer than we anticipate and prices rise more substantially. Central banks are likely to pay particularly close attention to what’s happening in labour markets. If policy is tightened more aggressively than we expect, it is likely to be because labour shortages have caused a larger and more sustained increase in wage growth. That risk is greatest in the US.

In case you missed it:

- We have revamped the Key Themes page of our website. This is the place where we bring together cross-cutting research on the key issues that will shape the global economic outlook. Keep an eye out for new themes as we add them over the coming months.

- Our Chief Commodities Economist, Caroline Bain, argues that speculation is now driving the price of natural gas and it’s only a matter of time before demand and supply adjust to bring them back down.

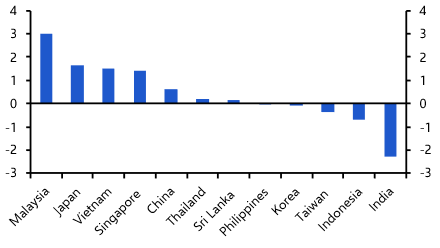

- Our Chief EM Economist, William Jackson, looks at the implications of China’s long-term property slowdown for other emerging economies.