Another week, another set of inflation figures to dial up the pressure on central banks. This time it was the ECB’s turn to feel the heat, with flash data showing that inflation hit 5.1% y/y in January. The culprit was a further rise in energy inflation, which is now running at a record 28.6% y/y. So, what’s behind the rise in energy inflation, and how should policymakers respond?

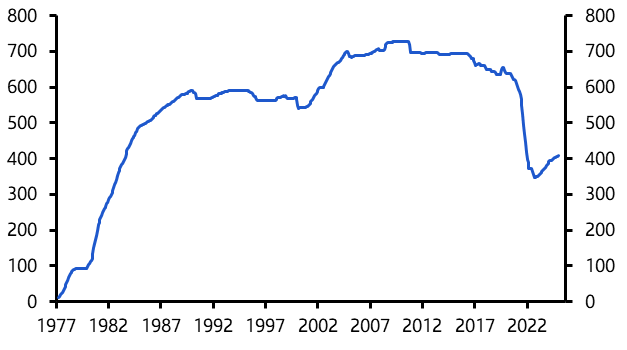

Let’s start with some basic facts. As I noted a few weeks ago, while services inflation is beginning to increase in several advanced economies, most of the increase in headline inflation over the past year has been driven by consumer goods and energy. In fact, as Chart 1 shows, energy alone has been responsible for around half of the increase in CPI inflation in advanced economies since the fourth quarter of 2020.

Chart 1: Contribution to Headline Inflation in Major DMs (%-pts)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

However, while energy inflation has increased in every major economy, the increase has been particularly acute in Europe. As Chart 2 shows, energy is now contributing almost 3%-pts to annual inflation in the euro-zone. And while energy’s contribution to overall inflation is currently lower in the UK, it will jump in April when the increase in the cap on household utility bills that was announced by the government last week will come into effect. In contrast, energy is adding (only!) 2%-pts to headline inflation in the US. More importantly, its contribution is now starting to fall.

Chart 2: Contribution of Energy to Headline Inflation in Selected DMs (%-pts)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

So while energy has been a source of higher inflation in every advanced economy, it is now a particular problem for the euro-zone and the UK. This explains why the issue of rising household energy bills has suddenly become a political hot potato for European governments.

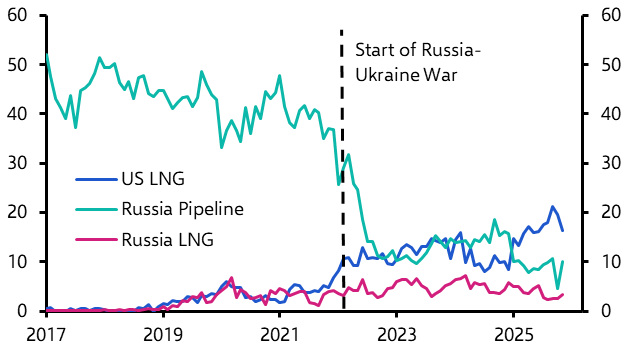

The reason why it has become more of a European problem has to do with what’s happening in global energy markets. Different grades of oil trade at different prices, but since oil can be shipped to different markets, prices do not tend to differ substantially between regions. The same is not true of natural gas. While LNG can be shipped, most gas is transported through fixed pipelines. This means that prices can differ considerably between regions depending on local demand and supply conditions.

As Chart 3 shows, while the price of WTI crude (the main US benchmark) and Brent crude (the European benchmark) have both increased by around 70% since the start of last year, increases in natural gas prices have varied substantially. In Asia and the US, benchmark natural gas prices have increased by 70% and 100% respectively since the start of last year. In Europe, however, they have increased by over 300%. The reasons are manifold but are mainly to do with supply: stocks are low, and a tendency to source gas on short-term contracts has made it difficult for governments to secure additional supply as demand has surged. In addition, the crisis in Ukraine has threatened European gas supplies and added a considerable premium to market prices. Crucially, natural gas prices tend to be the main determinant of household energy bills.

Chart 3: Increase in Prices of Selected Commodities since 1st January 2021 (%)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

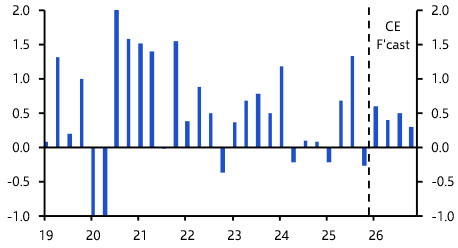

So what comes next and how should governments and central banks respond? When it comes to inflation, the key point to keep in mind is that it is the rate of change in prices – not the level – that matters. Accordingly, even if oil and natural gas prices remain flat at their current elevated level, energy’s contribution to headline inflation will drop back over the course of this year. (See Chart 4.)

If our forecast for modest falls in oil and gas prices is borne out then energy’s contribution to inflation will drop more quickly but, frankly, the change in prices from this point doesn’t make a great deal of difference. The key is that the large increase in prices in 2021 will gradually drop out of the annual comparison this year, causing energy inflation to drop back. Even in a “high price” scenario, in which oil and gas prices increase further, energy’s contribution to overall inflation falls back towards the end of this year.

Chart 4: Contribution of Energy to Headline Inflation in Major DMs (%-pts)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Inflation shocks caused by energy prices pose three challenges for policymakers. First, there’s not much that monetary policy can do to influence energy prices. Second, while a rise in energy prices increases inflation in the short-term, all other things being equal, the subsequent squeeze on real incomes is disinflationary over the medium-term. Finally, since lower income households spend proportionally more of their income on energy, higher energy prices can have significant distributional consequences.

The squeeze on real incomes – and the disproportionately large hit to lower- and middle-income households – has led to a series of measures by European governments to mitigate the effects of higher energy prices. This has taken different forms. The UK has announced a rebate on household utility bills; Spain has cut taxes on energy bills and introduced a windfall tax on energy companies; and France has introduced a cap on energy bills until (conveniently) April’s presidential election has passed.

Fiscal measures to cushion the hit to real incomes can be justified if governments believe that the energy shock is temporary, and prices will ultimately drop back. But they can create problems for governments if prices remain elevated. A permanent increase in energy prices implies a permanent deterioration in the terms of trade of economies that are net energy importers. Someone must ultimately bear this cost. This leaves a difficult choice: should policy support be withdrawn, causing a squeeze on real incomes that hits the poorest hardest, or should it be kept in place indefinitely incurring a permanent fiscal cost and distorting consumer behaviour? More often than not the laws of politics dictate that the path of least resistance will be taken.

Meanwhile, central banks should look through the immediate effects of higher energy prices on inflation and instead focus on the “second round” effects – that is to say the indirect impact they have on activity and inflation further down the line. In its latest forecasts released last week, the Bank of England argued that the squeeze in real incomes in 2022-23 would cause inflation to undershoot its target in 2024 if interest rates were increased in line with market expectations. Perhaps. But there is an alternative scenario, which is that, against a backdrop of tight labour markets, higher energy prices fuel higher pay demands and create a more sustained impulse to inflation. In normal times, central banks should largely ignore the ebb and flow of global energy prices. In today’s conditions, however, the latest rise in energy prices may strengthen the case for higher rates.

In case you missed it:

- Our proprietary dashboard shows that, while product shortages in G7 economies remain high, they have started to ease in recent weeks.

- Our Senior Asia-Pacific Economist, Marcel Thieliant, argues that the profit margins of Japanese manufacturers are on track to hit a record high.

- Our Chief Markets Economist, John Higgins, examines the threat to US Treasuries from inflation hysteresis.