Fracturing is going mainstream. We argued last year that we were entering a new era of global fracturing, in which the world’s major economies coalesce around rival blocs. Since then, a debate has picked up about what will follow this most recent phase of globalisation.

The IMF highlighted the risks of what it called “Geo-economic fragmentation” in a report earlier this month and ‘Co-operation in a fragmented world’ was billed as the theme of this year’s meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos.

But the debate that has been happening has been incomplete on two important counts. The first relates to the underlying driver of fracturing, and the second relates to the size and scale of the rival blocs that are likely to emerge. Both will have a significant bearing on macro and market outcomes – and will shape how events unfold in 2023.

Globalisation’s false promise

To understand what’s driving fracturing, we need to wind the clock back several decades. The era of globalisation that reshaped the world economy in the 1990s and 2000s was underpinned by a belief that economic integration would cause China and the former Eastern Bloc countries to become strategic partners with the West. This led to the widespread liberalisation of trade, capital and labour flows, and the globalisation of production, finance and ideas. But the economic reality has fallen short of the optimistic vision set out by Western leaders in the 1990s. Rather than becoming a strategic partner, China has instead emerged as a strategic rival to the US.

It is this strategic rivalry that now lies at the heart of global fracturing. It will, in our view, force other countries to pick sides such that the world splinters into two blocs: one that aligns primarily with the US and another that aligns primarily with China. Policy choices within these blocs will be shaped increasingly by geo-political considerations.

This provides a useful framework through which to consider the consequences of fracturing. Fracturing is too often talked about as a challenge to overcome, rather than something many are pushing for. By the same token, however, fracturing won’t simply result in the reversal of globalisation. Viewed through the lens of geopolitics, a wholesale reorganisation of global supply chains is unlikely. There are no compelling geo-political reasons why the US or Europe should stop importing the majority of consumer goods from China. Roll the clock forward ten years and it is likely that the West will still be buying toys and furniture from China.

Instead, fracturing between the blocs will take place along fault-lines that are geo-politically important. Production may shift locations, but only for goods that are deemed to be strategically significant. This is likely to include those with substantial technological and/or intellectual property components: think batteries, biotechnology, and high-end engineering products. What’s more, in cases where production does shift location, it is likely to be to other low-cost centres that align more clearly with the US. There will be no great “reshoring” of manufacturing jobs.

Size matters – but so does composition

This brings me to the second important point that has been missing from the recent debate: there is a significant difference between the size, scale and composition of the respective blocs that are likely to emerge as a result of fracturing.

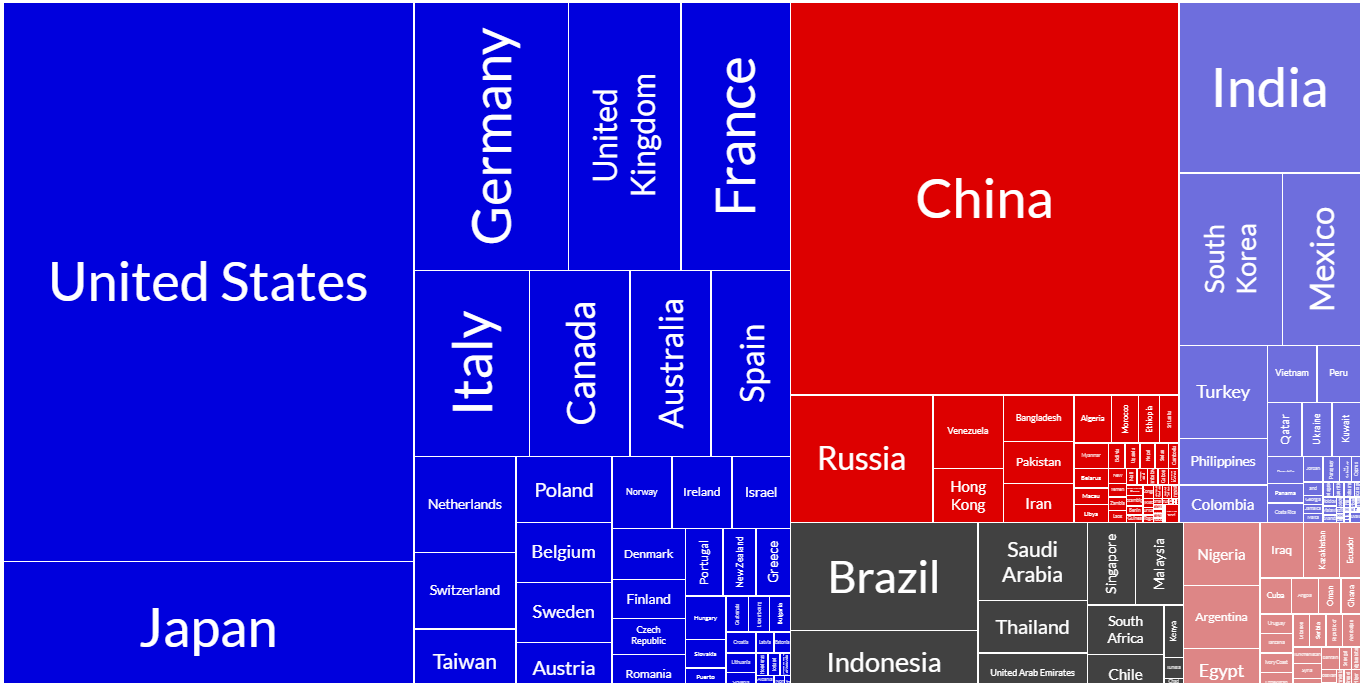

As part of our project on fracturing, we analysed everything from trade and financial dependencies to voting records at the UN in order to determine which countries would align with the US and which with China. This laid bare the fact that the global economy is not splitting down the middle. The major economies, apart from China, are almost all close allies of the US. In contrast, economies that align with China are smaller and tend to be commodity producers. That makes the US bloc both larger in terms of GDP but also more economically diverse than the China bloc. (See Chart 1.)

|

|

|

|

| Sources: IMF, Capital Economics |

This is important because it means that the US and its allies are better placed to be able to adapt to the challenges posed by fracturing. Where supply chains need to move, production can be shifted to a friendly country such as Mexico, Vietnam or Poland. Meanwhile, the sheer size of the US bloc is one important reason why the dollar will remain the world’s reserve currency and the US financial system will continue to provide the plumbing for the global economy.

In contrast, the relative lack of economic diversity among the economies that align with China will make it harder for it to adapt. Strong allegiances with large commodity producers give China the edge on securing supplies of important commodities, including those minerals needed for the green transition. But outside of China itself, there are no major high-tech producers, manufacturers or innovators within its bloc. This will make it harder for China to withstand supply chain of financial dislocation caused by fracturing, and places even greater pressure on a centralised model of growth that is already coming under severe strain.

Fracturing delayed?

The uneven nature of fracturing has been almost entirely absent from recent debate but it will have an important bearing on how events play out from here. Indeed, a recognition of these challenges facing China may explain the shift in tone by Beijing in recent months. Zhao Lijian, a combative “wolf warrior” spokesperson at the Foreign Ministry, has been side lined, and key figures within the leadership have adopted a more conciliatory approach towards the US. US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken will visit Beijing next month, and China’s top diplomat Wang Yi will tour European capitals in an effort to warm relations.

None of this means that Xi Jinping has jettisoned a long-standing ambition to overturn US hegemony. But the need for China to buy time to adapt to the challenges posed by fracturing could help to slow the process in 2023. In a world short of good news, this would count as a positive development. But it takes place against a backdrop in which the fundamental drivers of fracturing remain in place.

What you may have missed:

- We discuss fracturing in this week’s podcast episode, along with the impact of housing downturns on the timings of central bank pivots. Listen to it here.

- Markets Economist Adam Hoyes explored whether China equities valuations are still appealing in the wake of the reopening rally.

- Marcel Thieliant, the head of our Japan coverage, explained why we think the Bank of Japan will ditch Yield Curve Control in April.