Finally, some good news on the inflation front. But signs of cooling consumer and producer price pressures in the US are unlikely to silence the vigorous debate among economists about what central banks will still need to do to bring inflation back down to more comfortable levels.

It’s a debate that was triggered by a paper by Olivier Blanchard, Larry Summers and Alex Domash which argued that a large increase in unemployment will likely be needed to bring US inflation back to target. Others have since piled in, including a rebuttal co-authored by Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller.

It’s also a debate focused largely on demand dynamics, with arguments on both sides presented with strident confidence. But the current state of the global economy necessitates incorporating how supply side factors will evolve to understand what will bring inflation back to target – alongside a good deal of humility in recognising the extreme levels of uncertainty.

Demand side doesn’t tell the whole story

Over the past two years the global economy has been hit by two huge shocks, with the COVID-19 pandemic quickly followed by the war in Ukraine and subsequent surge in global energy and food prices. This has resulted in world economic conditions that are highly unusual in several important respects.

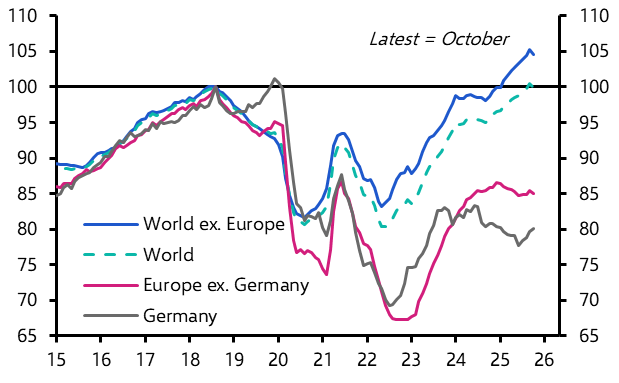

On the one hand, labour markets are extremely tight and inflation is running at rates last seen four decades ago. But both GDP and employment in advanced economies are running below their long-run trends. (See Charts 1 & 2.) This unusual state of affairs, and the absence of sufficient historical parallels, means we should be much less confident than usual in our forecasts – and that’s even before we consider the possibility of new shocks, such as an escalation in tensions between China and Taiwan.

Chart 1: G7 GDP (Q4 2019 = 100)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Chart 2: G7 Employment (Q4 2019 = 100)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

This debate has also thrown up the need for a fresh way of thinking following the shocks of the past two years. Economists tend to focus on issues affecting the demand side of economies, such as interest rates, fiscal policy and consumer spending. But the twin shocks of the pandemic and the Ukraine war primarily affected the supply side of economies. Lockdowns created extreme dislocation in the supply of goods and labour. The war in Ukraine has done the same to the supply of key commodities, particularly European natural gas.

Accordingly, any analysis of the inflation outlook is incomplete without sufficient focus on supply factors.

Enter the hockey stick

To that end, our Chief US Economist Paul Ashworth recently presented a simple framework for thinking about the current economic juncture. In this framework, the aggregate demand curve slopes down and the aggregate supply curve is shaped like a hockey stick. When output is below potential, firms produce any amount of goods and services at the prevailing market price. But when output reaches potential, the price demanded by firms to supply more starts to increase sharply. (See Chart 3.)

Chart 3: Aggregate Demand and Supply Framework

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Accordingly, when output is below potential, shifts in demand create potentially large changes in output but relatively small changes in price. But when output reaches potential, shifts in demand generate small changes in output but potentially large changes in price – in either direction.

There have been two pronounced shifts within this framework over the past couple of years. First, the aggregate demand curve has shifted out, say from AD1 to AD2, due in part to the boost from fiscal stimulus and loose monetary policy. Second, the aggregate supply curve has shifted in, say from AS1 to AS2, as dislocation in labour and product markets have reduced supply potential. As a result, economies have moved from an equilibrium position of A to an equilibrium position of B – output has increased modestly but prices have increased a lot.

This suggests that economies may have shifted to the vertical part of the aggregate supply curve, where small moves in output can generate big moves in prices. A small but telling example of this phenomenon can be seen in used car pricing in the US. While prices kept falling between 2014 and 2019 despite solid increases in demand, only a small increase in real consumption during the pandemic was enough to trigger a massive price surge as supply constraints bit.

Accordingly, it may only take a modest fall in demand to produce a significant drop back in price inflation. Used car prices could soon be falling outright, on this basis.

What’s more, policymakers may also get a helping hand from the supply side as labour market participation in the US and hours worked in Europe continue to rebound, and global supply chain problems ease. This would shift the aggregate supply curve back towards AS1 from AS2, meaning that an even smaller moderation of demand would be needed to bring down price inflation.

Reason to be cheerful?

Of course, this is only a simple framework for thinking – knowing exactly where different economies sit within it is impossible in real time. What’s more, central banks will still need to bear down on demand in order to bring inflation closer to target and prevent price expectations from becoming unanchored. In every major economy, with the exceptions of Japan and China, we think that interest rates will need to be raised above their neutral level. Economic growth will need to slow significantly and unemployment is likely to have to rise in order to cool red-hot labour market conditions. We continue to forecast recessions in the euro-zone and the UK (although this is due in part to the huge negative terms of trade shocks that both economies have experienced, not just the effects of tighter monetary policy).

But the global economy is currently in an unusual position and all forecasts are subject to high levels of uncertainty. There’s no question that central banks will need to dampen demand in order to tame inflation, but it’s unclear by how much. If we are on the vertical part of the aggregate supply curve, it’s possible that inflation can be brought under control with only a relatively small moderation in demand and rise in unemployment.

In a world short of good news, that possibility alone is one worth cheering.

In case you missed it:

- Our Chief Europe Economist Andrew Kenningham assesses the risks to the euro-zone economy from a termination of Russian gas imports. (To discuss this with Andrew and his team, register for a drop-in this Thursday.)

- And if that wasn’t enough, we’ve also explored the risks to German industry from low water levels in the Rhine river. (Spoiler: it’s bad, but nowhere near as big a problem as the gas crisis.)

- Our Senior Markets Economist, Jonathan Petersen, argues that the resilience of the Canadian Dollar is unlikely to last.