The key message to come from meetings of the Federal Reserve and Bank of England last week, and the European Central Bank the week before, was that the war in Ukraine has not deterred central bankers from their plans to tighten policy. In fact, both the Fed and the ECB delivered hawkish surprises.

The war has added to the squeeze on real incomes in advanced economies and caused a substantial tightening of financial conditions in Europe. But, for now, central banks remain focussed on bringing down inflation and containing any second-round effects on wages and prices. This is, on balance, the correct judgement. As we noted last week, while the economic outlook is unusually uncertain, the high starting point for inflation – and the likelihood that it will rise further – justifies a tightening of policy.

With that said, the more aggressive hikes in interest rates that are now being forecast by Fed officials have raised concerns that, by focussing on inflation, policymakers could end up tipping the economy into recession. This in turn raises the more general question as to whether, given the headwinds posed by the war in Ukraine and the spread of the Omicron variant in China, recoveries in major advanced economies are strong enough to withstand monetary tightening.

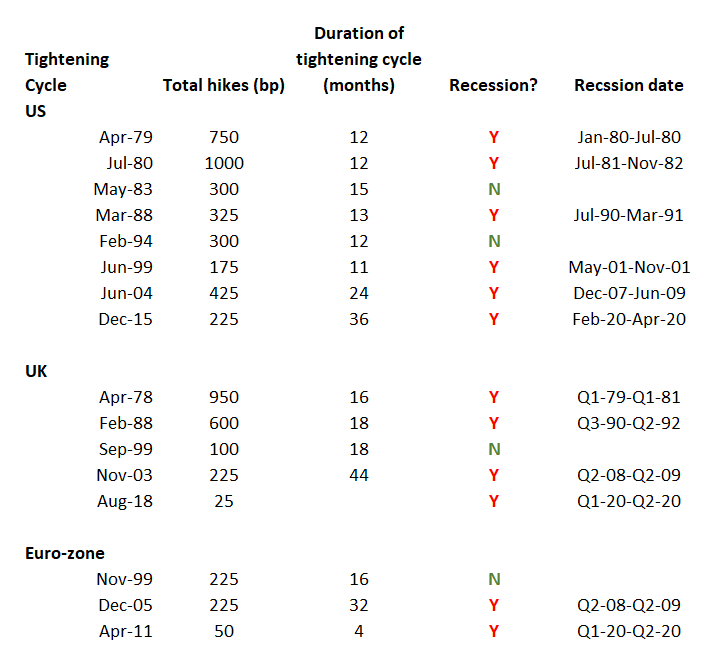

The lessons from history are troubling. Since the late-1970s there have been eight tightening cycles in the US and five in the UK. The ECB only came into being in 1999 and since then has been through three tightening cycles. This makes 16 tightening cycles in total – 13 of which have ended in recession. (See Table.) Soft landings are hard to achieve.

Table: Previous Tightening Cycles in US, UK and Euro-zone

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

The fact that tightening cycles have tended to end in recession could be interpreted as a reason for delaying or slowing the pace of tightening now. But this would be wrong.

There have been three reasons why tightening cycles have been followed by recession. The first is that economies have been hit by an exogenous shock. This was the case in 2020, when the pandemic (rather than the central bank tightening) caused a collapse in activity.

The second reason is that policy tightening has been either too slow or too timid to prevent economies overheating and/or bubbles inflating. These bubbles have then burst, causing an economic downturn. This was true of the global financial crisis in 2007-08, and also the dot-com crash in the US in 2001.

The final reason is that central banks allow inflation to spiral out of control – and then have to tighten policy aggressively, and drive the economy into recession, in order to bring it back down. This was the case in the late-70s and early-80s.

It is the third of these concerns that is now motivating the actions of central banks. Delaying rate hikes due to fears about the economic spillovers from the war in Ukraine would risk inflation becoming more entrenched – meaning more policy tightening is ultimately needed to squeeze it out of the system, and making a recession at some point in the future even more likely. By tightening now, central banks are attempting to follow a “stitch in time saves nine” approach to monetary policy.

The question is whether their actions will create a recession anyway? While the labour market is difficult to read right now, our base case is that interest rates will need to be increased by around 200-300bps in the US and UK – and by much less in the euro-zone – in order to return inflation to 2-3% by the end of central bank’s policy horizons. This would be much less than the increases of 600-1000bps that were needed in the early 1980s.

Accordingly, it is still possible to believe in a soft landing. But history shows that the path to a soft landing is narrow – and the inflation shock from the war in Ukraine has narrowed it further.

Even before the war, we thought that economic growth would be weaker than most expected this year. It is now likely that growth will be even softer this year, and that in the euro-zone and UK it will slow to a crawl in the second and third quarters. In these circumstances it wouldn’t take much to blow recoveries off course and generate a quarter or two of economic contraction. None of this means a recession is inevitable, or even likely. But in European economies, recessions have moved from a tail risk to a plausible scenario that market participants need to consider.

Former Fed Chair Paul Volcker, reflecting in 2013 on his now-lauded inflation fight of the late-70s and early-80s – a fight that dragged the US economy into two recessions – told an interviewer: “It’s much easier to lower interest rates than it is to raise interest rates, I think it’s fair to say, in almost any circumstances”.

While his successor Jerome Powell spoke confidently last week of the US economy’s ability to absorb monetary tightening, the fact remains that he and other global central bankers are now trying to achieve something that the historical record suggests is more likely to fail than succeed.

But it also suggests the costs of failing to act now may be greater.

In case you missed it:

- Our Senior China Economist, Julian Evans-Pritchard, argues that the latest COVID outbreak will derail China’s domestic recovery…

- …while our Chief China Economist, Mark Williams, takes stock of the risks to global supply chains.

- Finally, we have developed a range of proprietary dashboards to help clients track the fallout from the war on everything from financial conditions to the oil market. You can download them, and embed them in your own work, here.