There’s a dirty secret at the heart of economics: economists – and by extension central banks – understand less about inflation dynamics than we would like to admit.

Granted, we can model with reasonable accuracy what is likely to happen to fuel and food prices based on what’s happening in global commodity markets. And we have lots of charts to illustrate how inflation is likely to evolve over relatively short time frames.

But the fundamental drivers of inflation over longer periods are less well understood. This is evident in how the prevailing approach to thinking about – and managing – inflation has shifted over time.

Moving targets

In the 1970s, a monetarist revolution led by Milton Friedman argued that inflation was “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, and that bringing it to heel simply required governments and central banks to control the supply of money. Friedman’s doctrine had a significant influence on policy. In 1975 the Fed began to publicly announce targets for money growth. Four years later, the new UK government under Margaret Thatcher put in place targets for the growth of the broad money supply stretching over several years.

But the monetarist revolution ran into two problems. First, it turned out that in practice central banks had relatively little control over the broad money supply. And second, it quickly became clear that demand for money balances shifts for different reasons and in ways that do not necessarily affect inflation. By 1981, UK inflation had fallen sharply despite the fact that growth in the broad money supply had accelerated. Monetarism lost its allure as an anchor for policy. In October 1982, the Fed began to de-emphasize its targets for M2 growth. The Bank of England followed suit in 1983.

The framework that has dominated policymaking for the past three decades or so has two intellectual underpinnings. The first is that independent central banks should anchor long-term inflation expectations (and therefore price setting behaviour) by committing to keeping inflation at a low but positive rate of 2% or so. The second is that they should then set interest rates to control the balance of demand relative to supply (i.e. the output gap) such that they hit their inflation targets.

When demand outstrips supply, unemployment falls, and wages and prices rise. In response, central banks tighten policy in order to take some heat out of the economy and return inflation to target. Conversely, when demand undershoots supply, unemployment increases, disinflation (or outright deflation) becomes the dominant concern and central banks stimulate demand by loosening policy. Inflation fluctuates over the cycle, but because expectations are anchored it never takes off on a sustained basis. Instead, it fluctuates around the central bank’s target.

Central bankers in a bind

The problem with this framework, however, is that it assumes there is a stable relationship between aggregate demand, aggregate supply, wages and prices, and that central banks can therefore predict where inflation is heading and respond accordingly. But in reality these relationships are anything but stable.

Recent experience in the US illustrates this point. The unemployment rate in October was 3.7% – the same rate that it was in September 2019. But while the employment cost index (our preferred measure of wage growth) grew at 5.3% y/y in Q3 of this year, it was running at only 3.0% y/y in Q3 2019.

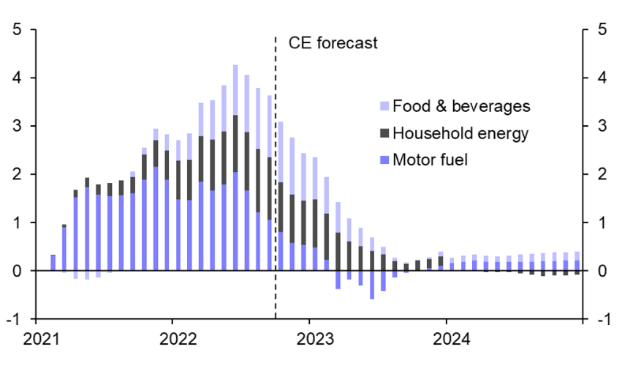

All of this leaves central banks in a bind. They can be fairly sure that headline inflation rates will fall over the coming quarters as this year’s energy and food price shocks start to drop out of the annual comparisons. The contribution of energy and food to headline inflation in advanced economies is likely to fall from over 4%-pts in the middle of this year to less than 0.25%-pts by mid-2023. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Contributions of Energy & Food Inflation to Major Advanced Economy Headline Rate (%-pts) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

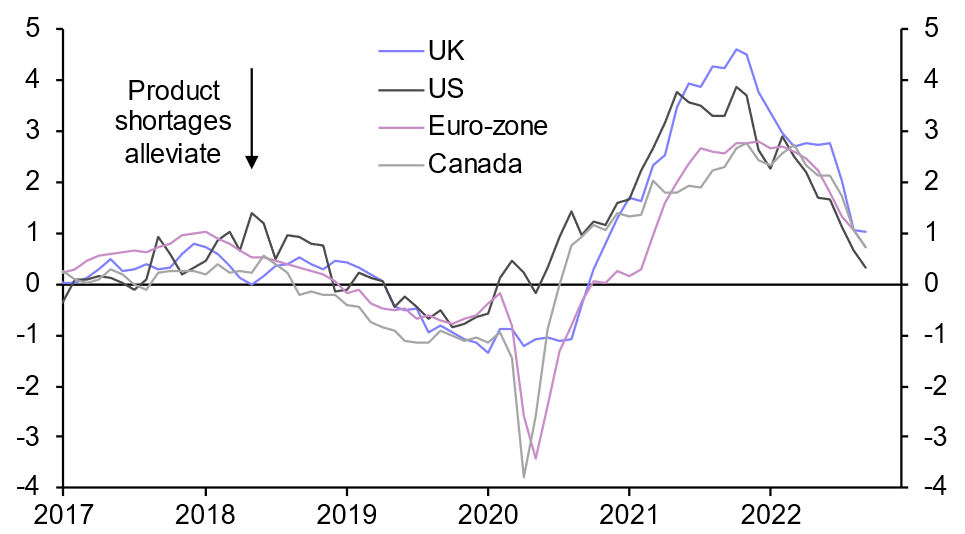

Likewise, there is mounting evidence of goods deflation. Supplier delivery times have collapsed and shipping costs have dropped by around 40%. Our proprietary indicator of goods shortages has fallen sharply. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: CE Product Shortages Indicators (Z-Scores) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

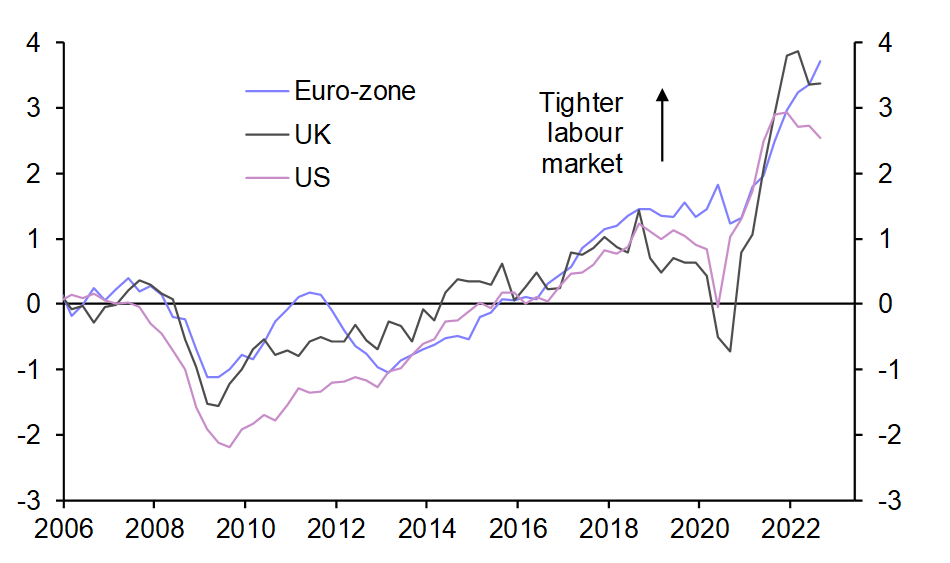

But the key for central banks is knowing how far inflation will fall, and for how long it will then stay there. On this, they can be much less certain. A lot will depend on what happens to labour market conditions and wage-setting behaviour. This is highly uncertain. The best we can say is that there has been a modest loosening of labour market conditions in the US and UK, and that conditions in the euro-zone are still tightening. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: CE Labour Market Slack Indicators (Z-Scores) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

But it is unclear how demand for labour will respond to the increases in interest rates that have already happened, and the ones that are coming down the track. There are even bigger questions about how labour supply will evolve as pandemic-related distortions fade. All of this makes it extremely difficult to judge how wage pressures will evolve – and how seriously central banks should take the threat of a price-wage spiral caused by a de-anchoring of expectations.

One consequence of this is that central banks are putting less weight on their forecasts and more on actual inflation. In a speech last week, Joachim Nagel, head of the Bundesbank, said that “we are seeing our economic models come up against their limits”. Isobel Schnabel, an Executive Director at the ECB, recently said that in these circumstances “current inflation outcomes provide additional, useful information”. Never mind anchoring inflation expectations – there’s a growing sense that there’s now little anchoring actual policy.

What does all of this mean for the economy and financial markets? There are two immediate consequences. First, without the conviction of a model or a set of reliable forecasts, it’s unlikely that central banks will be able to accurately flag a peak in rates – much less a pivot – in advance. Second, since monetary policy operates with a lag, putting more weight on actual inflation rather than the likely future path of inflation raises the risk of over-tightening.

Put simply, if central banks don’t know how far to raise rates to squeeze out inflation then there’s something wrong with our current thinking about what drives it.

In case you missed it:

- Our UK team explained UK Chancellor Hunt’s dilemma in our Autumn Statement preview. We’ll be briefing on the statement in a Drop-In on Thursday (register here).

- After the Dollar Index’s biggest one-day drop in nearly seven years, our FX Markets service outlined why we don’t think the dollar’s bull run is over yet.

- Why can’t China just ditch zero-COVID? The latest episode of our new podcast explains. Click here to listen and to subscribe via Spotify, Apple and Google.