One source of inflation concern over the past six months has been the growing evidence of supply shortages in key goods markets. These shortages have affected everything from semiconductors to household appliances, and they have fuelled fears that increases in consumer goods prices will follow.

At the heart of the problem has been the enormous shift in consumer spending during the pandemic. Spending on services collapsed as leisure and hospitality sectors were closed and travel restricted. But spending on consumer durables surged as people stayed at home and bought goods online. And as supply struggled to keep pace with the surge in demand, shortages emerged.

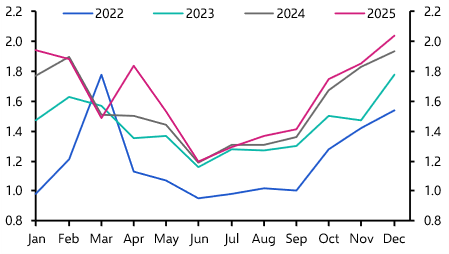

These shortages were in evidence once again in June’s PMI surveys released last week. Supplier delivery times increased across most manufacturing sectors in Asia (see Chart) and the output balance fell back in China. This echoes the message from the latest activity data. Industrial production in both Korea and Japan fell in May with auto manufacturers, which have borne the brunt of semiconductor shortages, hit particularly hard. In Japan, production of “transport equipment” fell by 16.6% m/m.

Chart 1: PMI Supplier Delivery Times

Sources: Caixin, Markit, Capital Economics

All of this will reinforce concerns that supply is failing to keep pace with red-hot demand and provide more grist to the inflation mill. But digging a little deeper there are early signs that shortages in some parts of global manufacturing may start to ease over the coming months.

The same survey of Japanese manufacturers that revealed a sharp fall in output in May also showed that producers are expecting a sharp rebound in production in the coming months. Carmakers are predicting output to have jumped 14.2% jump in June followed by another 7.9% rise in July. And while this may simply reflect over-optimism about future prospects, it could equally be the first sign that firms now expect some of the shortages of key inputs that have been weighing on production to ease. Media reports suggest that car firms expect semiconductor supply to begin to increase from around now.

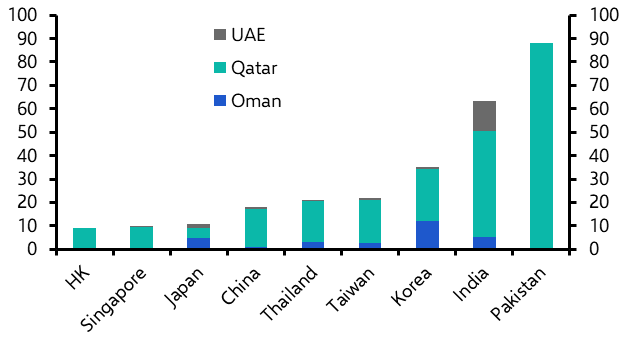

Meanwhile, there is also some evidence that global demand for consumer durables is peaking. The new exports orders sub-index of the official China PMI survey fell to a 12-month low in June. What’s more, China’s “industrial sales for exports”, another measure of export orders, levelled off in May and export orders for Taiwan also appeared to have plateaued in the past couple of months. (See Chart 2.)

Chart 2: Taiwan Exports and Orders ($, seas. adj., 2019 average = 100)

Source: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

Admittedly, there remains a backlog of orders that will take time to clear. The gap between the lines in Chart 2 can be thought of as proxy for unfulfilled orders. Factories will be busy meeting them for several months. Meanwhile, inventories have to be rebuilt along the supply chain. Retail inventories in the US are now at a record low relative to sales. (See Chart 3.)

Chart 3: US Retail Inventories/Sales Ratio

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

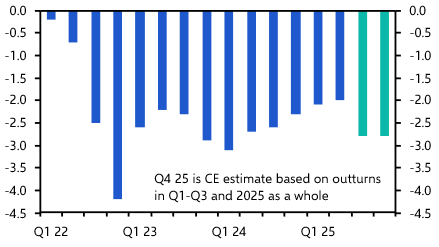

Accordingly, supply shortages are not going to disappear overnight – on the contrary, they are likely to persist in some form until well into 2022. But there are at least reasons to think that the extreme crunch in autos will now ease, and that supply shortages in other sectors will start to diminish over the second half of this year. That in turn should start to ease concerns that goods shortages will contribute to a broader rise in global inflation. Chinese factory gate prices for consumer durables and electronic goods increased at a record monthly pace in April, but the rate of increase slowed in May. (See Chart 4.) We suspect they will drop back further in the coming months. (June’s data will be released this Friday - as usual, our China service will cover the release in full.)

Chart 4: PPI – Durable Consumer & Electronic Goods (% m/m)

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics

There are, of course, other factors that could contribute to a build-up of inflation pressures. While goods shortages may start to ease, labour shortages are becoming more acute in most advanced economies. And while these too should eventually ease in most countries, we’ve outlined why there are more fundamental reasons to expect underlying inflation in the US to remain elevated.

Even so, compared to a few months ago, when every inflation indicator was pointing higher, any evidence that goods shortages are easing should at least provide some welcome relief to central banks.

In case you missed it (and some holiday reading for those of you in the US):

- Our Senior Markets Economist, Oliver Jones, assesses the likelihood that US antitrust policy becomes less favourable to Big Tech and sketches out the implications for equity markets.

- Our Head of Global Economics, Jennifer McKeown, sets out a framework for thinking about how the inflation threat and other factors will determine the path of monetary policy in the world’s major economies in the months ahead.

- Our Senior US Economist, Michael Pearce, argues that labour shortages in the US will persist into 2022.