Two major events have taken place in the world’s two largest economies over the past week. The first is the passage of President Biden’s $1.9trn stimulus bill in the US. The second is the meeting of the National People’s Congress in Beijing. Taken together, these have the potential to reshape the narrative around the post-pandemic recovery.

The story of the pandemic so far has been one of China’s economic outperformance. China managed to suppress the virus quickly, therefore negating the need for lengthy and widespread lockdowns. In contrast, other countries have struggled to get on top of the virus and have been in a state of intermittent lockdown for most of the past year. China has not only returned to its pre-virus level of GDP, but also its pre-virus trend of GDP. Meanwhile, every other major economy is still suffering from large shortfalls in output.

Yet events of the past week set the stage for a shift in the narrative.

In the US, not only is the size of the Biden stimulus huge, but it is coming at a time when rising vaccinations and falling virus numbers are allowing many states to ease restrictions on activity. The result is likely to be an upsurge in economic growth over the coming months and quarters. We expect the economy to expand by 6.5% this year – some way above the current consensus. In the process, US GDP is likely to blow past its pre-virus level by the end of the second quarter.

Meanwhile, one of the key messages to come from the National People’s Congress in Beijing was that policy support for China’s economy will be withdrawn over the course of this year. The activity data will continue to look extremely strong over the coming months. But this will be flattered by the practice of reporting and analysing Chinese growth rates in year-on-year terms (and the fact that the base for comparison this time last year was extremely depressed). Underlying momentum is already slowing, and the withdrawal of policy support means that this is likely to show up in the year-on-year growth rates over the second half of the year. With it, headlines about China’s outperformance are likely to fade.

As ever, the reality is more nuanced than the headlines suggest.

The fact that China’s economy is now back above its pre-virus path makes a slowdown in growth all but inevitable. At the same time, the fact that the US economy is still below its pre-virus path means there is significant scope for a rebound in output as the economy opens up. This is now being turbo-charged with additional stimulus.

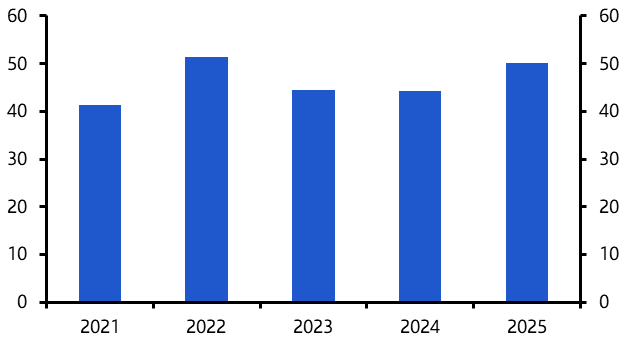

As we’ve noted before, the best way to judge the performance of different economies throughout the pandemic has been to focus on levels of output rather than growth rates. Viewed this way, China is still faring far better than any other major economy. (See Chart 1.) If growth slows over the course of this year, as we anticipate, then a more accurate interpretation would be that China is normalising rather than underperforming.

Chart 1: Change in Real GDP vs. Pre-virus level

The response of economic policymakers in China to the crisis was exemplary. Stimulus was large, quick and effective at shoring up aggregate demand. But the old problems that dogged China’s economy before the pandemic struck – over-investment, excess capacity and too much state intervention in the allocation of resources – have not gone away. In fact, in many ways the response to the crisis has made them worse. With the recovery from the crisis now complete, China is left facing the reality of structurally weaker growth.

This contains an important lesson for other economies: as the effects of the pandemic fade, old problems will start to resurface. The biggest challenge facing advanced economies prior to the pandemic was the extremely weak rate of productivity growth across the developed world. This had several causes, including low rates of business investment and the failure of new digital technologies to feed through into broad-based rises in productivity.

The consensus is that the pandemic has compounded matters by causing widespread economic scarring and a permanent hit to productivity. We have taken a more sanguine view of the long-term damage caused by the pandemic, but have stopped short of forecasting a significant boost to future productivity stemming from the pandemic. It is, however, possible that by spurring investment in new technologies and forcing firms to find new ways of working, the pandemic proves to be the spark that ignites a period of faster productivity growth in advanced economies.

In truth, these shifts will play out over years, not months, and it will be some time before we can judge the long-term impact of the pandemic. In the meantime, investors should prepare for a shift in the narrative around the recovery. They should be wary when headlines about China’s economic underperformance start to appear.

In case you missed it:

- Our Chief EM Economist, William Jackson, assesses fiscal vulnerabilities to higher interest rates in emerging economies.

- Our Chief UK Economist, Paul Dales, unpicks the collapse in UK-EU trade – and finds that some of the post-Brexit disruption is starting to ease.

- Our Senior Economic Adviser, Vicky Redwood, argues that one silver-lining of the pandemic may be that it accelerates efforts to green the global economy.